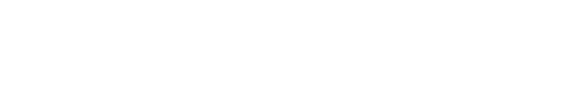

WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are warned that the following website contains images deceased persons.

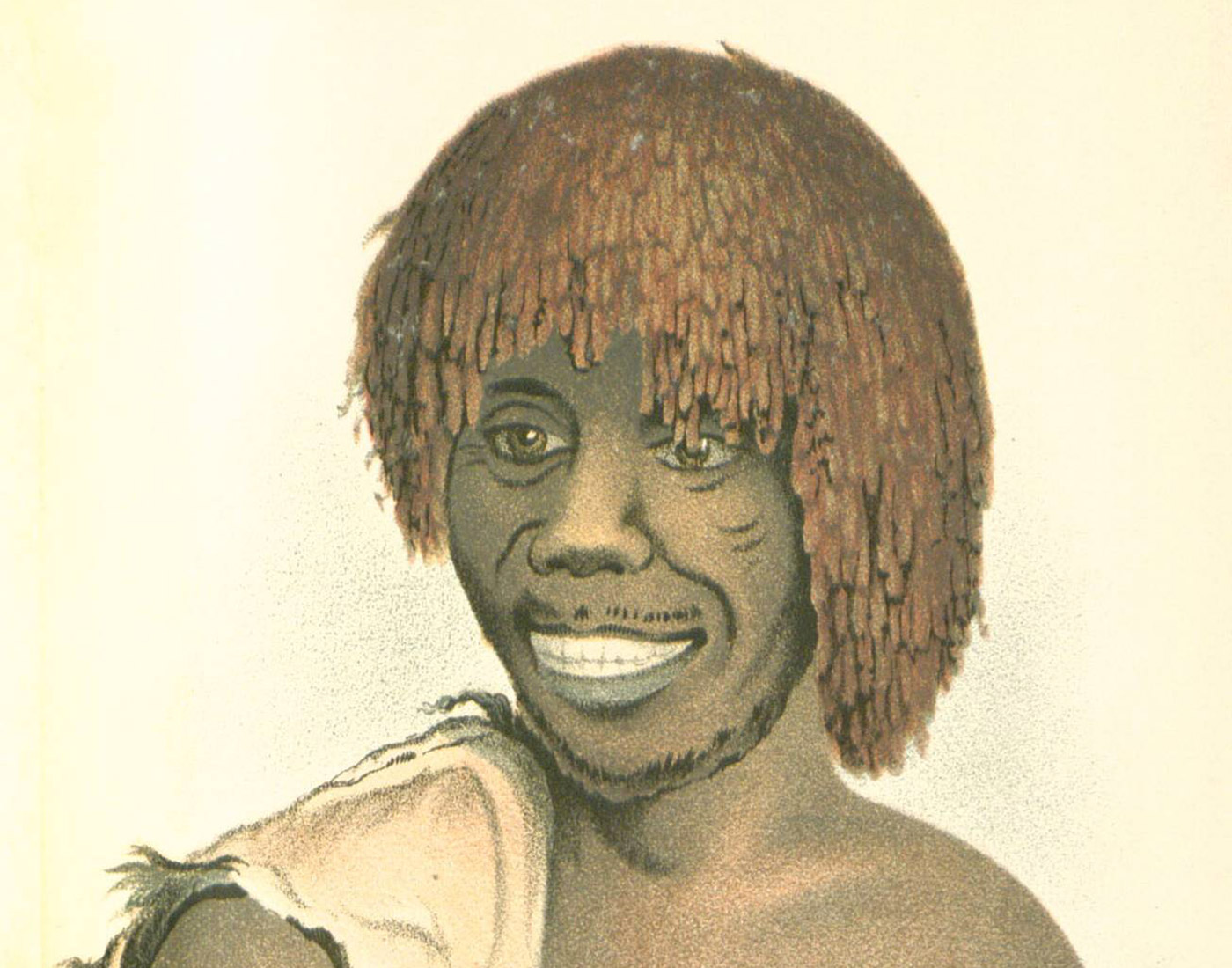

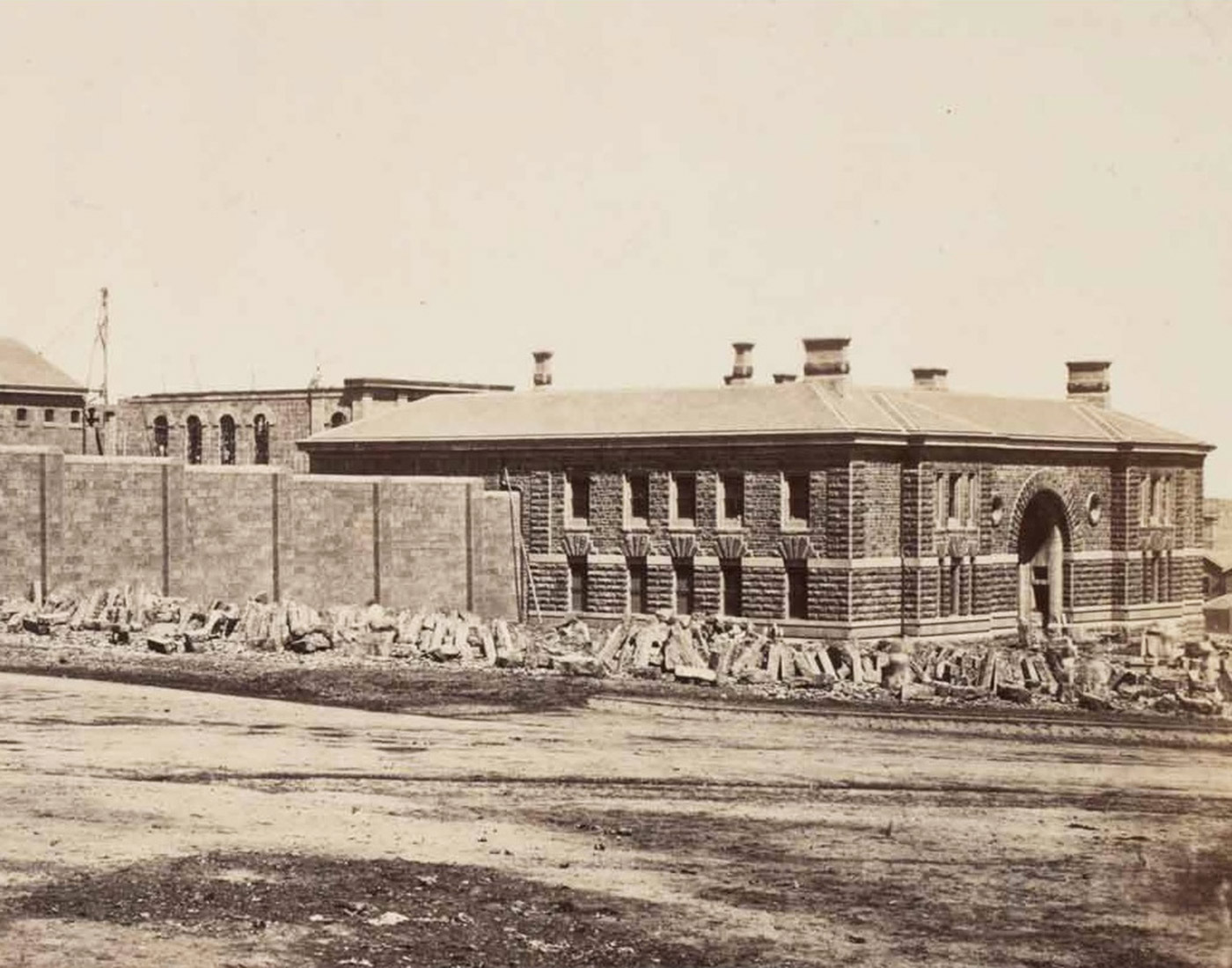

A small group of Tasmanian Palawa men and women were brought to Victoria by George Augustus Robinson, Chief Protector of the Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate, to help him subdue the Victorian Koori people. At Western Port Bay, five of the Tasmanians – Tunnerminnerwait, Maulboyheenner, Truganini, Planobeena and Pyterruner –joined the frontier wars wreaking violence across the District of Port Phillip. Two whalers were murdered by the group, for which Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner were hanged, despite the defence of Redmond Barry. Their executions on 20 January 1842, took place outside the Melbourne Gaol as Judge John Walpole Willis designed their punishment “to deter similar transgressions” by the local Koori people. Most of the Melbourne population turned out to watch as the two men slowly strangled to death in a bungled hanging. This clash between cultures led to five of the first nine executions in Victoria being of Aboriginal men.